There’s been a handful of articles critical of Google’s AppEngine that have bubbled up to the top of Hacker News lately. I’d like to throw our story into the ring as well, but as a story of a happy customer rather than a switcher.

We’ve been building out our product, Gri.pe, since last May, after pivoting from our previous project, DotSpots. The only resource available to develop Gripe in the early days was myself. I’d been playing with AppEngine on and off, creating a few small applications to get a feel for AppEngine’s strengths and weaknesses since its initial Python release. We were also invited to the early Java pre-release at DotSpots, but it would have been too much effort to make the switch from our Spring/MySQL platform to AppEngine.

My early experiments on AppEngine near its first release showed that it was promising, but was still an early release product. Earlier this year, I started work on a small personal-use aggregator that I’ve always wanted to write. I targeted AppEngine again and I was pleasantly surprised at how far the platform had matured. It was ready for us to test further if we wanted to tackle projects with it.

Shortly after that last experiment, one of our interns at DotSpots came to us with an interesting idea. A social, mobile complaint application that we eventually named Gri,pe. We picked AppEngine as our target platform for the new product, given the platforms new maturity. It also helped that as the sole developer on the first part of the project, I wanted to focus on building the application rather than spending time building out EC2 infrastructure and ops work that goes along with productizing your startup idea. I prototyped it on the side for a few months with our designer and once we determined that it was a viable product, we decided to focus more of the company’s effort on it.

There were a number of great bonuses to choosing AppEngine as well. We’ve been wanting to get out of the release-cycle treadmill that was killing us at DotSpots and move to a continuous deployment environment. AppEngine’s one-liner deployment and automated versioning made this a snap (I hope to detail our Hudson integration another blog post). The new task queue functionality in AppEngine let us do stuff asynchronously as we always wanted to do at DotSpots, but found to be awkward to automate with existing tools like Quartz. The AppEngine Blobstore does the grunt work of dealing with our image attachments without us having to worry about signing S3 requests (in fairness, we’re using S3 signed requests for our new video upload feature, but the Blobstore let us launch image attachments with a single day’s work).

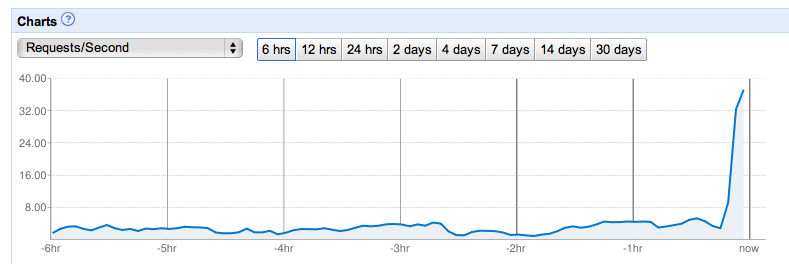

When it came time for us to launch at TechCrunch 50 this year, I was a bit concerned about how AppEngine would deal with the onslaught of traffic. The folks on the AppEngine team assured me that as long as we weren’t doing anything to cause a lot of write contention on single entity groups, we’d scale just fine. And scale we did:

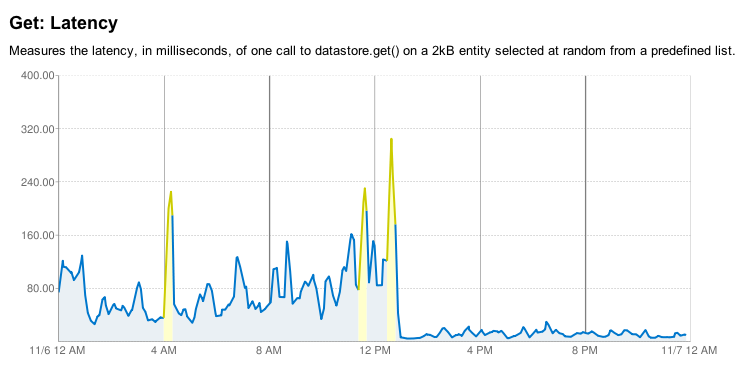

In the days after our launch, AppEngine hit a severe bit of datastore turbulence. There was the occasional latency spike on AppEngine while we were developing, but late September/early October was much rougher. Simple queries that normally took 50ms would skyrocket up to 5s. Occasionally they would even time out. Our application was still available, but we were seeing significant error rates all over. We considered our options at that point, and decided to stick it out.

Shortly after the rough period started, the AppEngine team fixed the issues. And shortly after that, a bit of datastore maintenance chopped the already good latencies down even further. It’s been smooth sailing since then and the AppEngine team has been committed to improving the datastore situation even more as time goes on (from here):

We didn’t jump ship on AppEngine for one rough week because we knew that their team was committed to fixing things. We’ve also had our rough weeks with the other cloud providers. In 2009, Amazon lost one our EBS drives while we were prototyping DotSpots infrastructure on it. Not just a crash with dataloss, but actually lost. The whole EBS volume was no longer available at all. We’ve also had weeks where EC2 instances had random routing issues between instances, instances lock up or get wedged with no indication of problems on Amazon’s side. Slicehost had problems with our virtual machines losing connectivity to various parts of the globe.

“Every cloud provider has problems” isn’t an excuse for any provider to get sloppy. It’s an understanding I have as the CTO of a company that bases its future on any platform. No matter which provider we choose, we are putting some faith in a third-party that they will solve the problems as they come up. As a small startup, it makes more sense for us to outsource management of IT issues than to spend 1/2 of an engineer’s time dealing with this. We’ve effectively hired them to deal with managing the hard parts of our scaleability infrastructure and they are working for a fraction of what it would cost to do this ourselves.

Putting more control in the hands of a third party means that you have to give up the feeling of being in control of every aspect of your startup. If your self-managed colo machine dies, you might be down for hours while you get your hands dirty fixing, reinstalling or repairing it. When you hand this off to Google (or Amazon, or Slicehost, or Heroku), you give up the ability to work through a problem yourself. It took some time for me to get used to this feeling, but the AppEngine team has done amazing work in gaining the trust of our organization.

Since that rough week in September, we’ve had fantastic service from AppEngine. Our application has been available 100% of the time and our page rendering times are way down. We’re committing 100% of our development resources to banging out new features for Gri.pe and not having to worry about infrastructure.

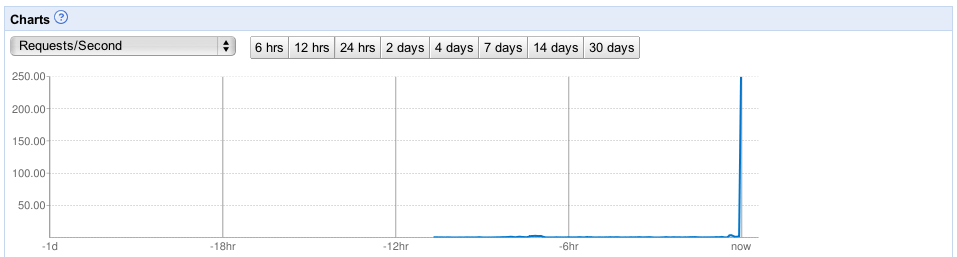

On top of the great steady-state service, we were mentioned on ABC’s The View and had a massive surge in traffic which was handled flawlessly by AppEngine. It transparently scaled us up to 20+ instances that handled all of the traffic without a sweat. In the end, this surge cost us less than $1.00:

There’s a bunch of great features for AppEngine in the pipeline, some of which you can see in the 1.4 prerelease SDK and others that aren’t publicly available yet but address many of the issues and shortcomings of the AppEngine platform.

If you haven’t given AppEngine a shot, now is a great time.

Post-script: We do still use EC2 as part of our gri.pe infrastructure. We have a small nginx instance set up to redirect our naked domain from gri.pe to www.gri.pe and deal with some other minor items. We also have EC2 boxes that run Solr to deal with some search infrastructure. We talk to Solr from GAE using standard HTTP. As mentioned in the article above, we also use S3 for video uploads and transcoding.

Follow @mmastrac on Twitter

Read full post