Erik at Carwoo posted an interesting codebreaking challenge to the Carwoo blog earlier today.

Erik at Carwoo posted an interesting codebreaking challenge to the Carwoo blog earlier today.

This particular challenge piqued my curiosity. One of my hobbies is rooting Android phones and I enjoy all sorts reverse-engineering problems. More importantly, this one happened to match up with some downtime I had this afternoon.

I fired up Python and quickly got to work. At my day job, Gri.pe, we use Java. I love Java as a development language, but I find that Python’s interactive mode is best for quickly experimenting with data in unknown formats. There’s a great deal of power in the standard Python libraries and it’s well-suited for quick byte and bit manipulation.

The first thing I did was to take a look at the individual bytes of the base64 decoded data:

>> min(s), max(s)

(32,90)

The range of 32 (‘ ‘) to 90 (‘Z’) suggested that the bytes had been coerced to a printable range from their natural, though binary-uncomfortable, base-59 representation. I worked from this part on assuming that this was true as it held for the challenge itself, as well as the various sample encodings:

>>> qbf

[1, 24, 38, 18, 30, 16, 43, 40, 15, 39, 35, 29, 28, 46, 48, 32, 33, 7, 19, 12, 45, 2, 1, 39, 4, 45, 45, 53, 23, 56, 41, 14, 47, 45, 23, 37, 47, 49, 34, 53, 43, 44, 13, 48, 54, 34, 30, 7, 22, 32, 52, 0, 27, 10, 13, 35, 51, 14, 21, 34, 5, 15, 27, 2, 44, 7, 47, 49, 31, 14, 6, 49, 3, 49, 24, 1, 25, 33, 15, 16, 55, 21, 46, 50, 20, 40, 6, 52, 19, 28, 32, 51, 20, 47, 14, 16, 12, 48, 15, 15, 42, 1, 21, 21, 17, 35, 21, 22, 7, 15, 22, 13, 49, 9, 23, 40, 9, 42, 27, 23, 20, 1, 25, 35, 57, 55, 34, 53, 16, 49, 55, 21, 17, 33, 55, 20, 18, 27, 13, 36, 7, 27, 47, 33, 40, 34, 29, 57, 55, 45, 38, 43, 46, 45, 23, 43, 22, 34, 30, 30, 30, 39, 0, 27, 42, 43, 54, 4, 41, 54, 20, 3, 42, 49, 29, 27, 56, 53, 6, 29, 11, 8, 57, 52, 32, 10, 7, 9, 11, 5, 2, 9, 2, 23, 12, 3, 39, 4, 56, 30, 18, 42, 52, 40, 2, 32, 1, 51, 12, 30, 53, 11, 52, 33, 54, 31, 22, 5, 9, 20, 54, 53, 18, 11, 28, 3, 9, 55, 18, 5, 29, 53, 49, 42, 40, 50, 23, 58, 34, 23, 43, 32, 31, 33, 19, 1, 2, 41, 14, 31, 42, 37, 17, 50, 42, 34, 12, 56, 5, 1, 38, 7, 31, 30, 44, 31, 29, 56, 56, 14, 7, 4, 50, 7, 56, 56, 2, 50, 8, 52, 33, 53, 14, 53, 16, 26, 23, 20, 26, 14, 2, 32, 25, 45, 25, 37, 47, 41, 39, 39, 26, 35, 25, 18, 31, 43, 58, 9, 34, 18, 57, 6, 30, 29, 55, 19, 42, 13, 42, 12, 6, 8, 53, 24, 7, 15, 40, 7, 23, 25, 58, 33, 53, 35, 53, 37, 28, 49, 32, 35, 43, 39, 24, 9, 56, 12, 25, 5, 28, 27, 31, 47, 48, 47, 43, 40, 51, 28, 16, 2, 58, 36, 33, 33, 53, 50, 25, 18, 1, 10, 28, 33, 39, 38, 45, 23, 10, 49, 23, 28, 12, 17, 50]

It didn’t appear to be a simple encoding as the number of bits wasn’t a nice, round number:

>>> len(qbf)/43.

8.9069767441860463

I explored the possibility that it was a base-59 encoded version of something as well, but nothing seemed to pop out (none of the base-59 numbers had promising base-2, 10 or 16 representations):

>>> reduce(lambda x,y: x*59+y, qbf)

41407517501859586326197566364505794272099644350300252534189551267025735776717090113531360628479958032951680470965566919981633022692412690504948993859533954300510015897257502231588804493684836579000834698632035250601929666970976653754473920192216650558365260965365239849090933529931468815659914090640650939870573055692803806368452144490717915923609157169530794000213060205251901007965316849847932159686920362166230161797107467060590682186205774757385089316643047935984486008508524050103003822235196827448543677268467374714192183904155940695587335521537764755681737258468452222357818887460237021822605843003409567903505844564024546249528549309875903061566053488229272080782809344L

>>> hex(reduce(lambda x,y: x*59+y, qbf))

'0xcc1f1f6b3bc02fff9273cd07bbc1f3e058998ab93854a79eb28981bb6d31f405e6c5d38c25bd13464a543eb781d735ec72f070039c9bfc4bc3753eca35a3cd282a43bf96989ffd0666827966f460f3aee7d7c420b7c71bdd02df4f2db6c96601c649cfdf27d31edd802aa9989a5b9ba8fdb96278d95b7b00ac31f24dc7ff2c42528aa18a5e124edc969ec2cb4821bd54cdc2b78dcad7e730269c9835ef44617d2c4ac78e4d278c431c76becdecfa549651cb2f71bb471e3ee5389fbba636e6d75f1bbc2c633006f47bc89a58fd22cd144c339af33965ecfa8a3bd6175cf128b206fcab0619f67fd3df0a668c100ee4124b3717a02c53b2c57475383b04a77822f43ce12d8ddbfe57f318566d1f5c407ad125982d574fb95900L'

>>> bin(reduce(lambda x,y: x*59+y, qbf))

'0b1100110000011111000111110110101100111011110000000010111111111111100100100111001111001101000001111011101111000001111100111110000001011000100110011000101010111001001110000101010010100111100111101011001010001001100000011011101101101101001100011111010000000101111001101100010111010011100011000010010110111101000100110100011001001010010101000011111010110111100000011101011100110101111011000111001011110000011100000000001110011100100110111111110001001011110000110111010100111110110010100011010110100011110011010010100000101010010000111011111110010110100110001001111111111101000001100110011010000010011110010110011011110100011000001111001110101110111001111101011111000100001000001011011111000111000110111101110100000010110111110100111100101101101101101100100101100110000000011100011001001001110011111101111100100111110100110001111011011101100000000010101010101001100110001001101001011011100110111010100011111101101110010110001001111000110110010101101101111011000000001010110000110001111100100100110111000111111111110010110001000010010100101000101010100001100010100101111000010010010011101101110010010110100111101100001011001011010010000010000110111101010101001100110111000010101101111000110111001010110101111110011100110000001001101001110010011000001101011110111101000100011000010111110100101100010010101100011110001110010011010010011110001100010000110001110001110110101111101100110111101100111110100101010010010110010100011100101100101111011100011011101101000111000111100011111011100101001110001001111110111011101001100011011011100110110101110101111100011011101111000010110001100011001100000000011011110100011110111100100010011010010110001111110100100010110011010001010001001100001100111001101011110011001110010110010111101100111110101000101000111011110101100001011101011100111100010010100010110010000001101111110010101011000001100001100111110110011111111101001111011111000010100110011010001100000100000000111011100100000100100100101100110111000101111010000000101100010100111011001011000101011101000111010100111000001110110000010010100111011110000010001011110100001111001110000100101101100011011101101111111110010101111111001100011000010101100110110100011111010111000100000001111010110100010010010110011000001011010101011101001111101110010101100100000000'

I also used numpy’s histogram function to see if there were signs of a simple substitution. While there were spikes of various values, nothing seemed to be significant when you compared the histograms of the various encodings of “THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG”.

The fact that more than eight output positions on average represented a single input position strongly suggested that there was some sort of reduction involved in decoding. I tried a number of different approaches with bit counting and different groupings, but none yielded any promising results.

The breakthrough came about a minute after Erik posted his last hint:

If you base64 decode this

IThGMj4wS0gvR0M9PE5QQEEnMyxNIiFHJE1NVTdYSS5PTTdFT1FCVUtMLVBW

Qj4nNkBUIDsqLUNTLjVCJS87IkwnT1E/LiZRI1E4ITlBLzBXNU5SNEgmVDM8

QFM0Ty4wLFAvL0ohNTUxQzU2Jy82LVEpN0gpSjs3NCE5Q1lXQlUwUVc1MUFX

NDI7LUQnO09BSEI9WVdNRktOTTdLNkI+Pj5HIDtKS1YkSVY0I0pRPTtYVSY9

KyhZVEAqJykrJSIpIjcsI0ckWD4ySlRIIkAhUyw+VStUQVY/NiUpNFZVMis8

IylXMiU9VVFKSFI3WkI3S0A/QTMhIkkuP0pFMVJKQixYJSFGJz8+TD89WFgu

JyRSJ1hYIlIoVEFVLlUwOjc0Oi4iQDlNOUVPSUdHOkM5Mj9LWilCMlkmPj1X

M0otSiwmKFU4Jy9IJzc5WkFVQ1VFPFFAQ0tHOClYLDklPDs/T1BPS0hTPDAi

WkRBQVVSOTIhKjxBR0ZNNypRNzwsMVI=

The first 5 characters are “!8F2>”

Those 5 characters represent the first “T”. Another “T” won’t necessarily result in the same code. Actually, the odds of ever seeing that code again for a “T” is low.

I ran through a few quick tests and discovered the first part of the solution: the sum of the first five characters, modulo 59, equalled the first character of the output!

>>> sum(qbf[:5])

111

>>> sum(qbf[:5])%59

52

>>> ord('T')-32

52

I went though the other versions of the sample encoding and saw that the same held for the first five digits. I checked the next five and didn’t see the correlation there. It also didn’t hold for the next six. The pattern *did* hold for the next seven. Even more tantalizing was that the challenge itself appeared to follow the same pattern:

>>> chr(sum(orig[:5])%59+32)

'D'

>>> chr(sum(orig[5:12])%59+32)

'O'

At this point I figured that I’d write a quick program to brute force the rest of the string.

#!/usr/bin/python

from base64 import *

qbf = [ord(x)-32 for x in b64decode("""IThGMj4wS0gvR0M9PE5QQEEnMyxNIiFHJE1NVTdYSS5PTTdFT1FCVUtMLVBW Qj4nNkBUIDsqLUNTLjVCJS87IkwnT1E/LiZRI1E4ITlBLzBXNU5SNEgmVDM8 QFM0Ty4wLFAvL0ohNTUxQzU2Jy82LVEpN0gpSjs3NCE5Q1lXQlUwUVc1MUFX

NDI7LUQnO09BSEI9WVdNRktOTTdLNkI+Pj5HIDtKS1YkSVY0I0pRPTtYVSY9 KyhZVEAqJykrJSIpIjcsI0ckWD4ySlRIIkAhUyw+VStUQVY/NiUpNFZVMis8 IylXMiU9VVFKSFI3WkI3S0A/QTMhIkkuP0pFMVJKQixYJSFGJz8+TD89WFgu

JyRSJ1hYIlIoVEFVLlUwOjc0Oi4iQDlNOUVPSUdHOkM5Mj9LWilCMlkmPj1X M0otSiwmKFU4Jy9IJzc5WkFVQ1VFPFFAQ0tHOClYLDklPDs/T1BPS0hTPDAi WkRBQVVSOTIhKjxBR0ZNNypRNzwsMVI=""")]

orig = [ord(x)-32 for x in b64decode("""QCgyPSghK1kwTlRJO0MrVTtZLUxWLCg3MypEUCNQJjNGTlMuIyU8TzwpSDNP ND0tRFg7RkUoJjotJzQwIz8pJUFCODtQI0AyPCFaTkNTUyQ/PUgqN0VKLCEi VUxWRjo2SUYnSiAiMkdGVCpGSCw+NDAqVyhUIEAtWTVMRiQzMi8jIiMuPyFP

V0k0MjlVOyQyTFM4VkgvQStRWkY3SEkwKDsqIzlFSjxHJS0+P0xTPDZIRSZW NVkvO0kuM1REJUkqMk8/Sz4tPy1JR04/WjM4V0ggVD8tU0JURDFBMCovMldO MzVVSjFDTjY0Lz00Ojc5UkZBSkMyUyxAOy05MCA5KyJXJVQ6KTZJTFJJL0pC

JyIkRCUiLkhOSTZJKyRDKC4qV0EuOz4qTVg/OypMUztAMTFLLzI8RU8+VVct OzQ+NEdIRUwm""")]

text = "THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG"

output = ""

i = 0

start = 0

text_i = 0

while True:

c = chr(sum(qbf[start:i])%59+32)

print sum(qbf[start:i]), c, text[text_i]

if c == text[text_i]:

print "Found at %d-%d %d" % (start,i,i-start)

output += chr(sum(orig[start:i])%59+32)

start = i

i = i + 4

text_i = text_i + 1

print output

i = i + 1

The output from this test program yielded most of the solution:

0 T

1 ! T

25 9 T

63 $ T

81 6 T

111 T T

Found at 0-5 5

D

153 C H

188 + H

217 H H

Found at 5-12 7

DO

187 * E

194 1 E

213 D E

225 P E

270 B E

272 D E

273 E E

Found at 12-23 11

DON

... [a few dozen lines snipped] ...

Found at 347-360 13

DON'T FORGET TO DRINK Y<-R OVALTIN9-

213 D D

Found at 360-365 5

DON'T FORGET TO DRINK Y<-R OVALTIN9-

104 M O

132 . O

165 O O

The solution wasn’t perfect at this point, but when you look at the output, the pattern becomes pretty clear:

Found at 0-5 5

Found at 5-12 7

Found at 12-23 11

Found at 23-36 13

Found at 36-41 5

Found at 41-48 7

Found at 48-59 11

Found at 59-72 13

Found at 72-77 5

Found at 77-84 7

Found at 84-95 11

Found at 95-108 13

From the pattern, I quickly whipped up a solution. It’s not the most elegant bit of Python, but the results are the most important part:

#!/usr/bin/python

from base64 import *

qbf = """IThGMj4wS0gvR0M9PE5QQEEnMyxNIiFHJE1NVTdYSS5PTTdFT1FCVUtMLVBW Qj4nNkBUIDsqLUNTLjVCJS87IkwnT1E/LiZRI1E4ITlBLzBXNU5SNEgmVDM8 QFM0Ty4wLFAvL0ohNTUxQzU2Jy82LVEpN0gpSjs3NCE5Q1lXQlUwUVc1MUFX

NDI7LUQnO09BSEI9WVdNRktOTTdLNkI+Pj5HIDtKS1YkSVY0I0pRPTtYVSY9 KyhZVEAqJykrJSIpIjcsI0ckWD4ySlRIIkAhUyw+VStUQVY/NiUpNFZVMis8 IylXMiU9VVFKSFI3WkI3S0A/QTMhIkkuP0pFMVJKQixYJSFGJz8+TD89WFgu

JyRSJ1hYIlIoVEFVLlUwOjc0Oi4iQDlNOUVPSUdHOkM5Mj9LWilCMlkmPj1X M0otSiwmKFU4Jy9IJzc5WkFVQ1VFPFFAQ0tHOClYLDklPDs/T1BPS0hTPDAi WkRBQVVSOTIhKjxBR0ZNNypRNzwsMVI="""

orig = """QCgyPSghK1kwTlRJO0MrVTtZLUxWLCg3MypEUCNQJjNGTlMuIyU8TzwpSDNP ND0tRFg7RkUoJjotJzQwIz8pJUFCODtQI0AyPCFaTkNTUyQ/PUgqN0VKLCEi VUxWRjo2SUYnSiAiMkdGVCpGSCw+NDAqVyhUIEAtWTVMRiQzMi8jIiMuPyFP

V0k0MjlVOyQyTFM4VkgvQStRWkY3SEkwKDsqIzlFSjxHJS0+P0xTPDZIRSZW NVkvO0kuM1REJUkqMk8/Sz4tPy1JR04/WjM4V0ggVD8tU0JURDFBMCovMldO MzVVSjFDTjY0Lz00Ojc5UkZBSkMyUyxAOy05MCA5KyJXJVQ6KTZJTFJJL0pC

JyIkRCUiLkhOSTZJKyRDKC4qV0EuOz4qTVg/OypMUztAMTFLLzI8RU8+VVct OzQ+NEdIRUwm"""

def decode(code):

values = [ord(a)-32 for a in b64decode(code)]

offsets = [5,7,11,13]*len(code) # note: won't need all of these, but guaranteed more than enough

decoded = ""

while len(values):

decoded += chr(sum(values[:offsets[0]])%59+32)

values = values[offsets[0]:]

offsets = offsets[1:]

return decoded

print decode(qbf)

print decode(orig)

The output, which I posted quickly to the blog and the HN story:

THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG

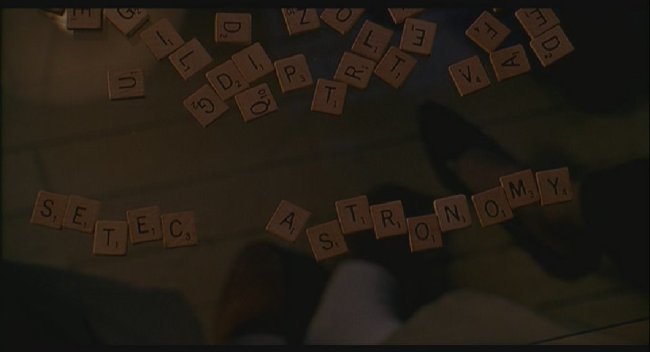

DON'T FORGET TO DRINK YOUR OVALTINE!

Read full post